The task of a jury member at the Eurovision Song Contest is pretty straightforward:

- Watch the Jury Show of the semifinal that your country is allocated to and submit a ranking of all the entries.

- Watch the Jury Show of the grand final and submit a ranking of all the entries.

However, it could also go like this:

- Watch the Jury Show of the semifinal that your country is allocated to and submit a ranking of all the entries.

- Notice that you had to rank them and not give them points, so you should have actually put a 1 next to your favourite song and not a 17, oopsie daisy.

- Watch the Jury Show of the grand final and submit a ranking of all the entries, feeling very smug this time because you actually understand the task description.

This is of course an entirely hypothetical scenario. As is widely known, jury members are highly vetted, specifically trained professionals. See, it’s even written in the jury member selection criteria:

Let’s call the mishap outlined above “blockhead voting”. A clever play on words on the term “bloc voting”, which is a fan favourite excuse for blaming the own country’s lack of success on external factors.

How would we go about finding cases of blockhead voting?

The Eurovision Song Contest is notorious for its plentitude of voting rule changes over the years. However, we do have detailed voting records for jury members since 2016 on eurovision.tv. This gives us data from 5 contests overall to work with, at the low cost of a bit of web scraping and a few hours of our life that we will never get back.

Now that we have the raw data, it is time to think about what we actually want to find.

Of course we have to work with a few assumptions:

People are inertial.

Assumption 1

Meaning, if a jury member liked a song in the semifinal, they will probably also like the song in the grand final, and give it a high score / low rank again. Also:

Love and hate are stronger than indifference.

Assumption 2

This is an extension to the first assumption. We expect the song a jury member placed on top of the list for the semifinal to be towards the top again for the grand final. The same is true for the end of the list – a bit weaker probably, since we likely lose the bottom half of the ranking when we go from the semifinal to the final. We also expect the order of the songs in the middle to be a lot more volatile.

And finally, a third assumption:

Most jury members are not blockheads.

Assumption 3

This might come to a surprise to some, but we expect most jury members to be able to follow simple instructions.

Our strong belief in Assumption 3 allows us to postulate that there is only a negligible number of jury members who filled out their scoring sheet in the wrong order. Therefore, the statistical properties of “correct” jury votes are roughly equal to the statistical properties of all jury votes. With this, we can try to confirm Assumption 1 and 2.

Checking our own assumptions

We begin by simplifying the data we work on.

After scraping, we have two rankings for each jury member:

- the ranking of the songs in their respective semifinal

- the ranking for the songs in the grand final.

Since ten songs advance from each semifinal to the grand final and you cannot vote for your own country, there are a total of nine songs which a jury member has ranked twice – or ten, if we are looking at a jury member from the so-called big five or the host country, who are pre-qualified for the grand final.

We will only focus on those songs that have been ranked twice. This simplifies things a lot.

Now for our assumptions. The average rank difference over all jury members and entries is 1.53, meaning that an entry on average gains or loses 1.53 ranks when comparing the semifinal to the final. If everyone just ranked the entries randomly, the average rank difference would be around 3.2. That seems to support assumption 1. Yay!

To investigate assumption 2, we are going to check how frequently an entry that gets ranked first or last in the semifinal also gets ranked first or last in the grand final1. It turns out that in 58 % of the cases, the entry ranked first is the same for semifinal and grand final, while this is only the case for 35 % of entries that are ranked second, and for 25 % of entries that are ranked third. A similar pattern can be observed for the end of the rankings: 44 % of entries ranked last for the semifinal are then also ranked last for the grand final, which is also true for 27 % of the second-to-last entries, and 22 % of the third-to-last entries. These findings seem to support assumption 2 well enough that we can continue with the most interesting stuff.

The most interesting stuff

We want to find suspicious rankings. It therefore makes sense to start by defining what we actually deem suspicious and what we deem innocuous. Since we don’t want to look through all 1029 jury members by hand, we also want an automated way to find the most suspicious candidates automatically. For this, we try to find a metric that gives the suspicious configuration the highest score and the innocuous one the lowest score. Since some jury members have ranked nine entries twice and some ten, it will probably make sense to normalise the resulting scores to account for that.

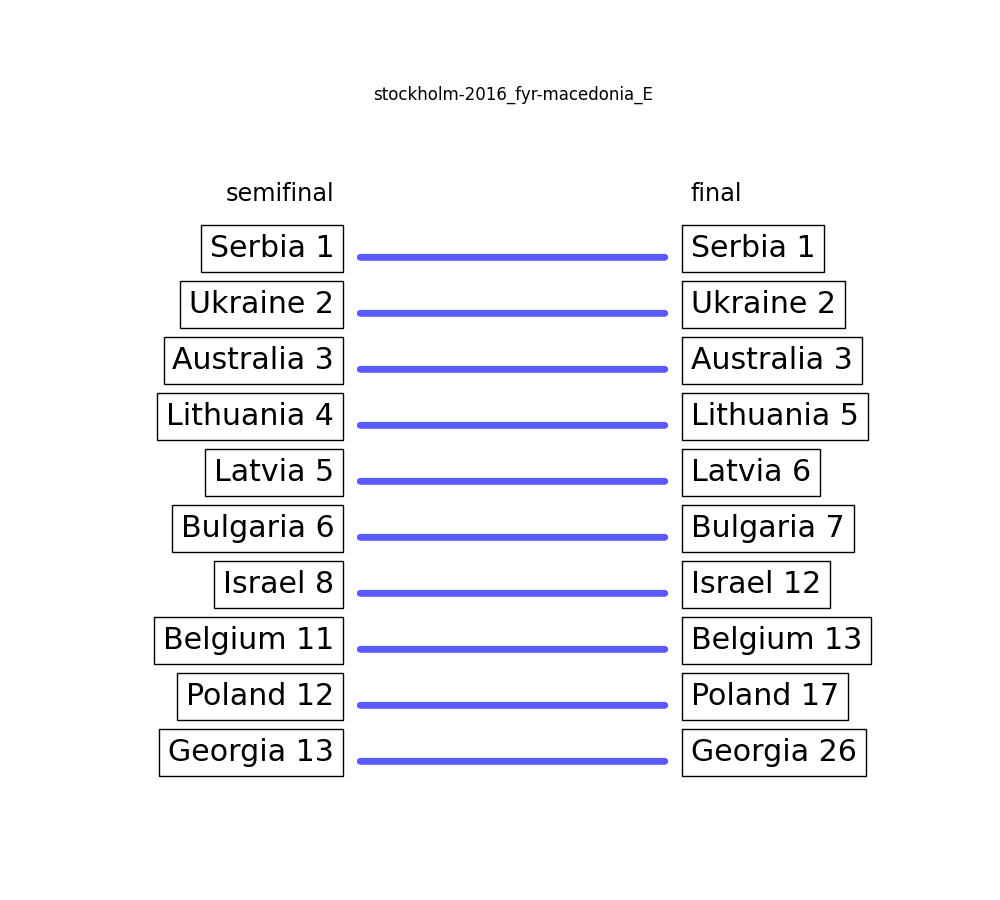

To demonstrate what’s suspicious and what is not, we will use Netherlands D from 2016 as an example. The internal order of the 9 songs that were ranked twice did not change at all between the semifinal and the final. In our world, that is as unsuspicious as it gets. If we then flip the order of the semifinal, we get the most suspicious ranking pattern ever™.

The concrete metric that we use does not matter too much since we will investigate the results manually anyway2.

The first thing we find are three more jury members who did not reorder their entries at all:

But we are of course interested in the other end of the list. Let’s have a look at all ten jury members who have scored at least 7 / 10.

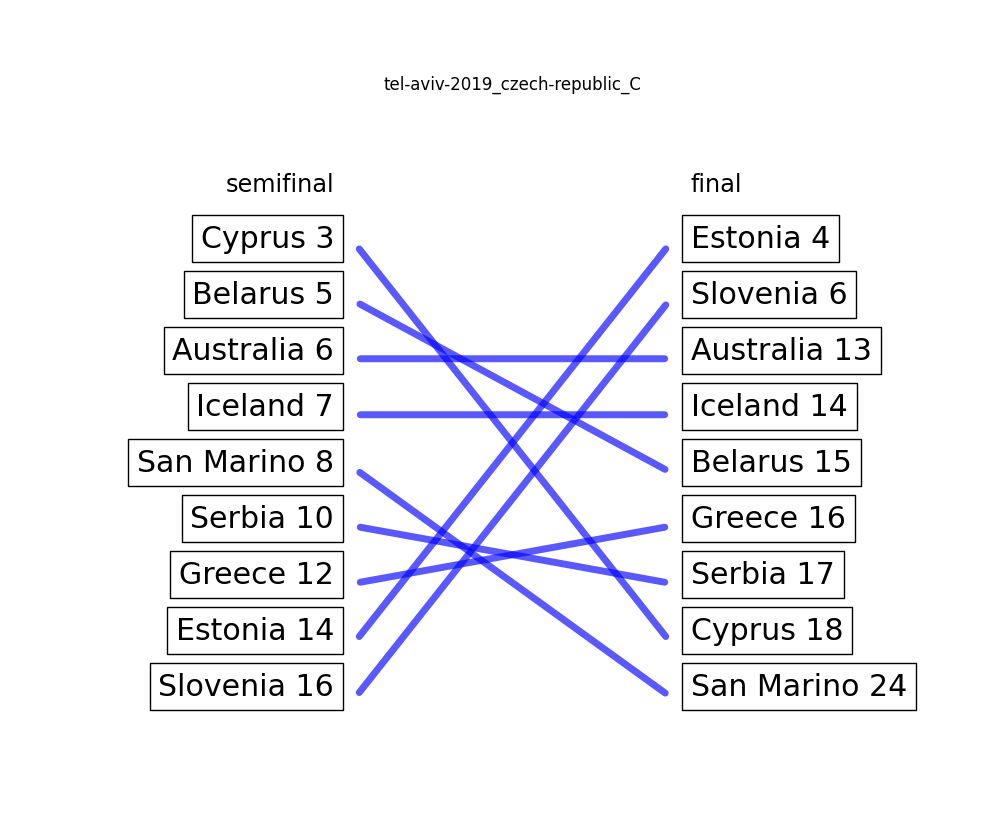

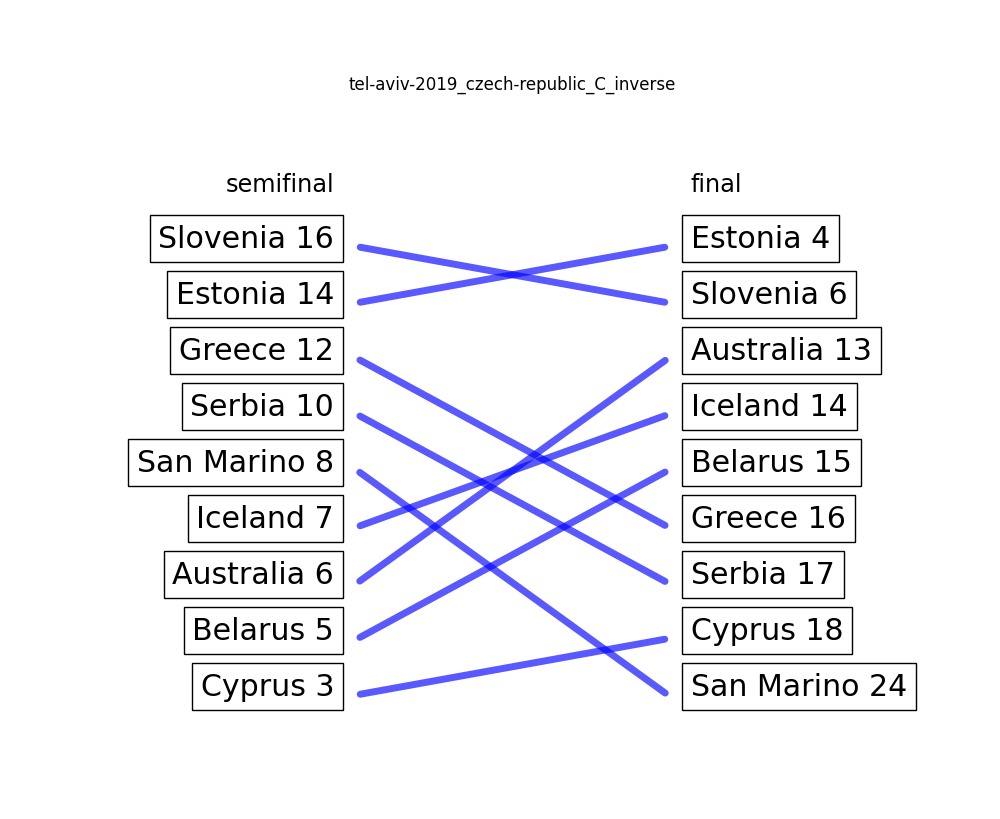

Tel Aviv 2019: Czech Republic C – 7.25 / 10

Looks a bit fishy, right? Especially those two first places once you invert the semifinal? Well: Dear readers, we gottem. A certified Blockhead. Plus, we have an indicator that our filtering method might actually work well enough to generate some results.

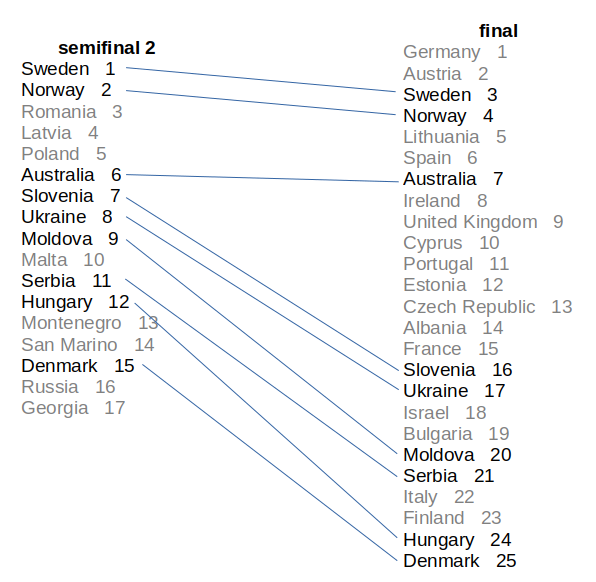

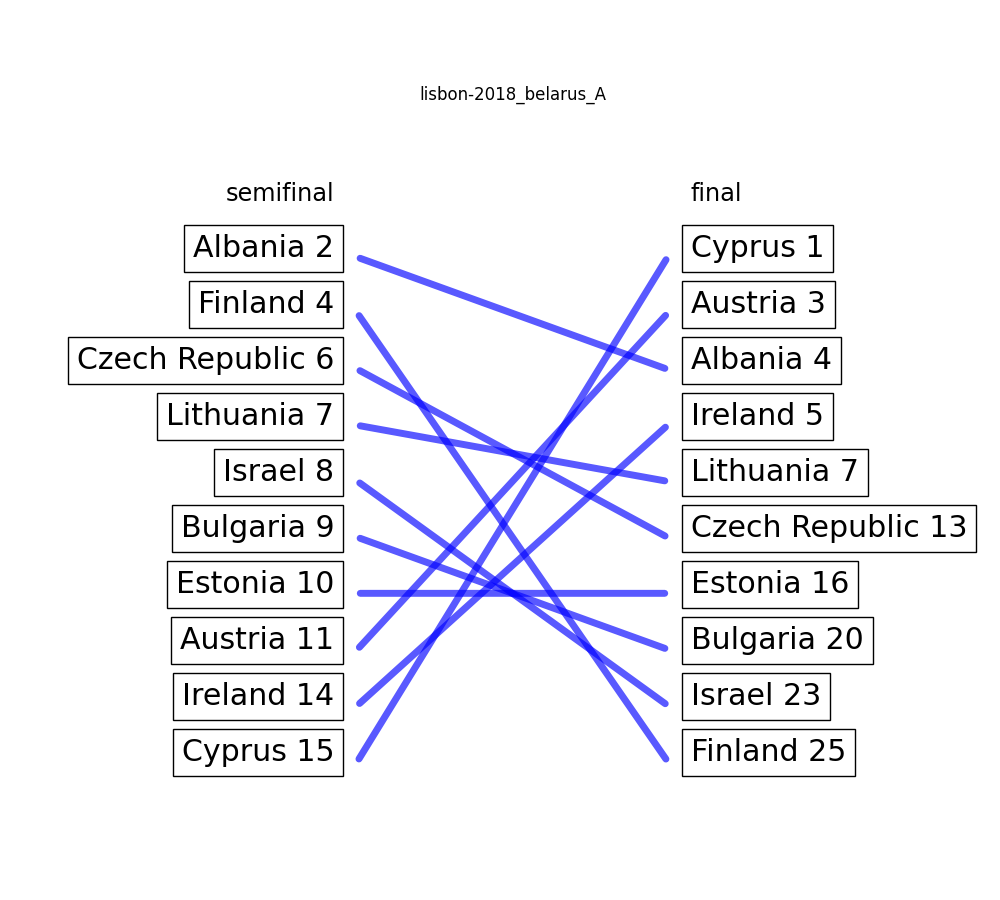

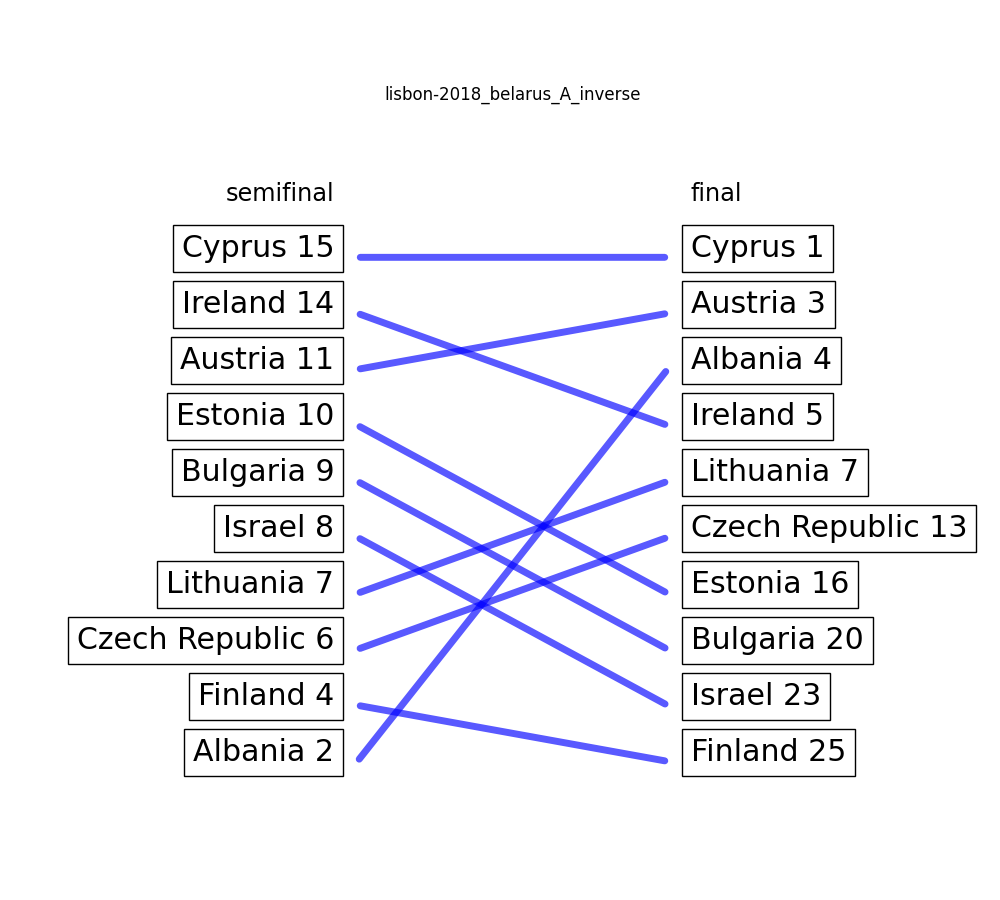

Lisbon 2018: Belarus A – 7.27 / 10

Once again, there is a suspicious diaginal line in the actual voting behaviour from the bottom of the semifinal to the top of the final, and vice versa. This time though, no article on eurovoix (that I know of).

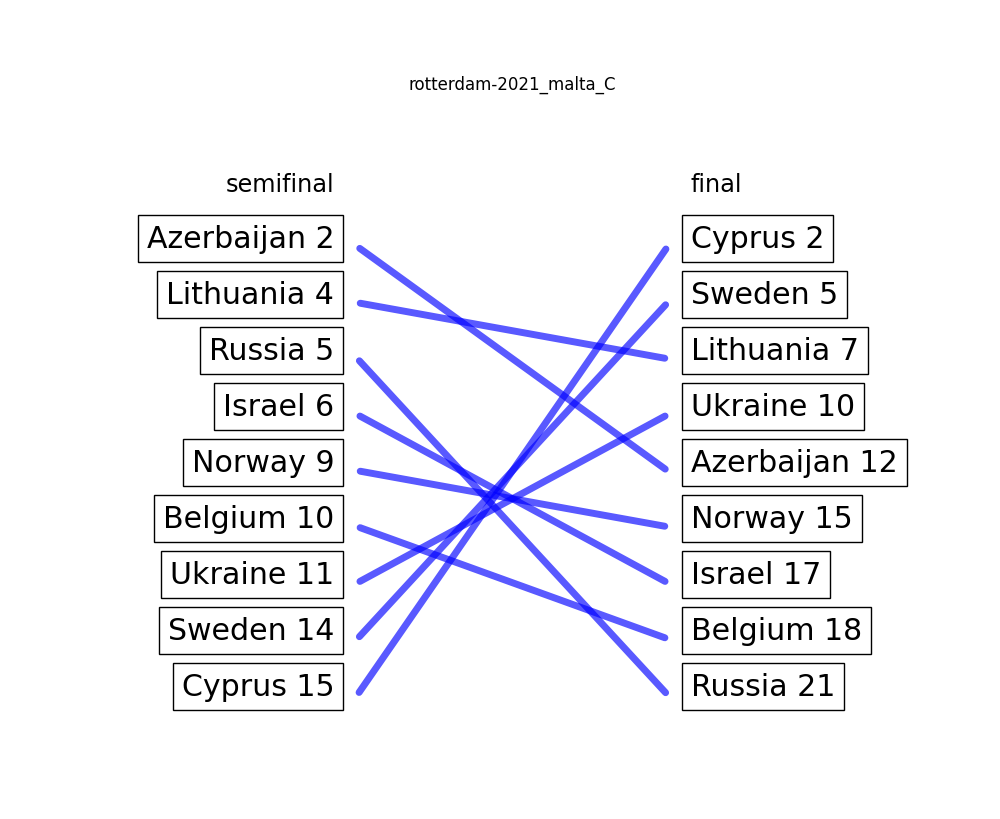

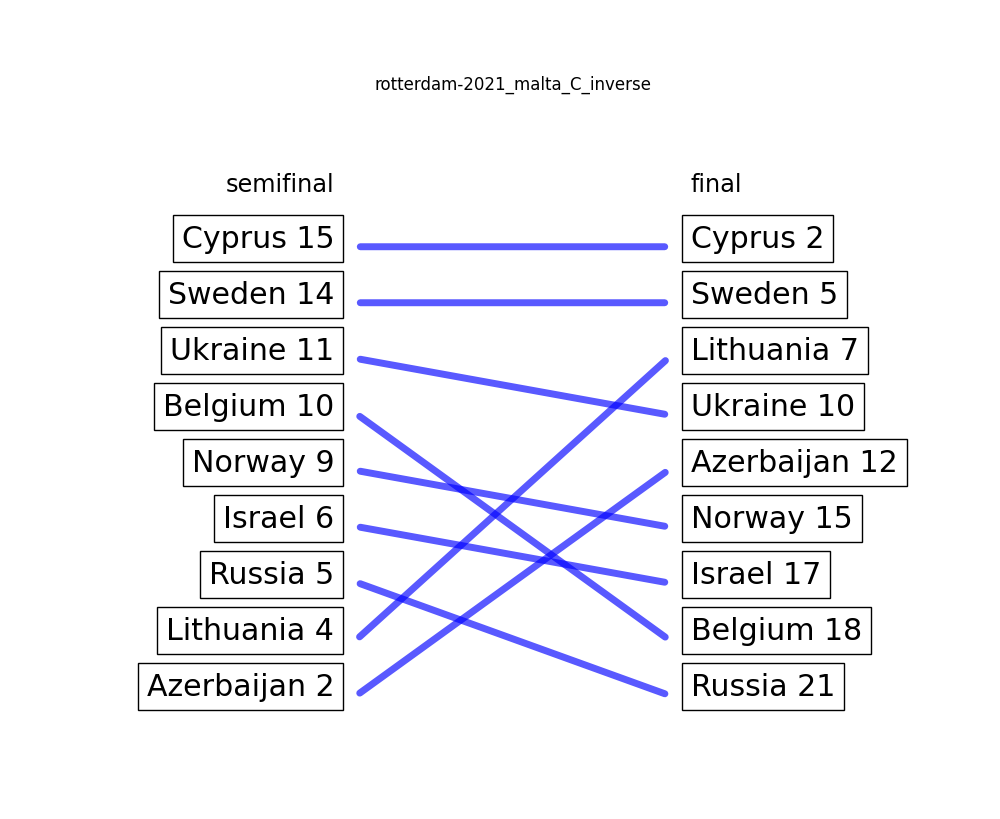

Rotterdam 2021: Malta C – 7.33 / 10

There seems to be a recurring pattern here, where the last ranks in the semifinal suddenly become the first ranks in the final. How could that be? I wonder.

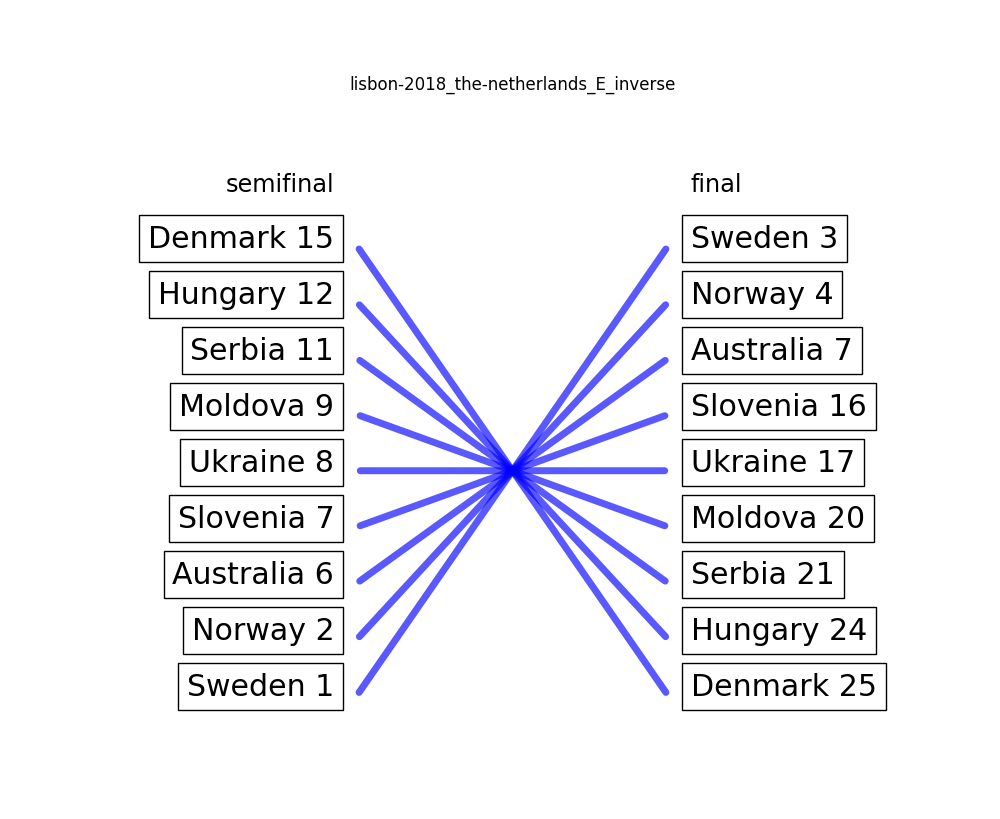

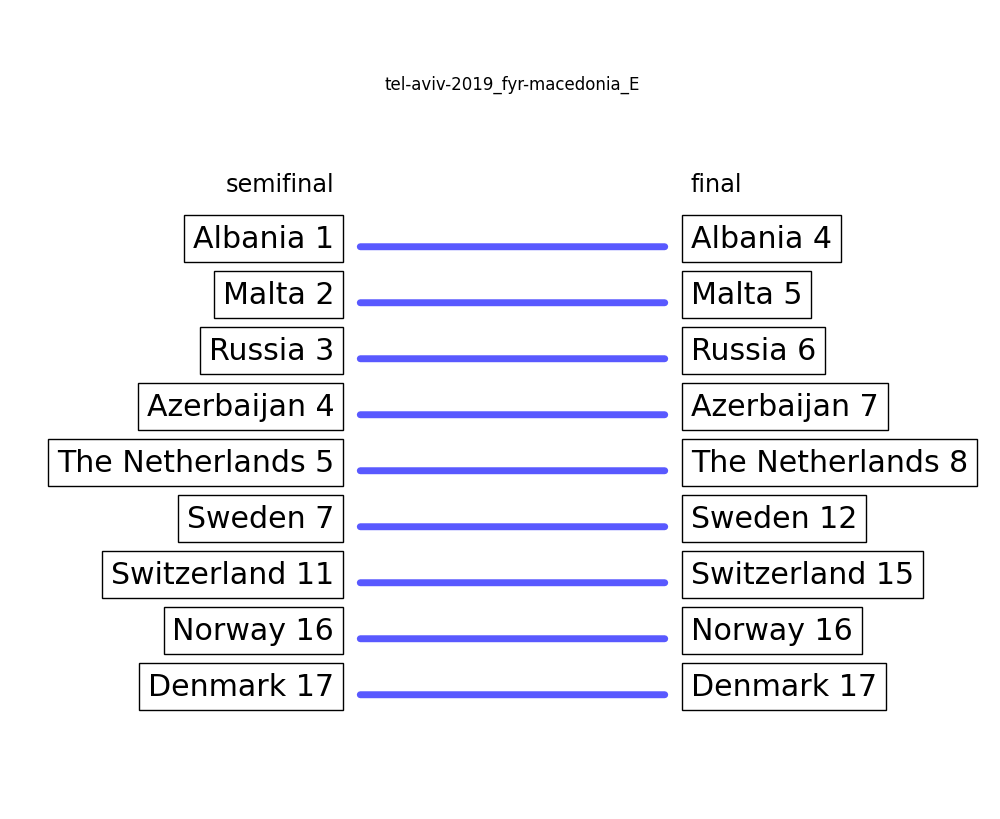

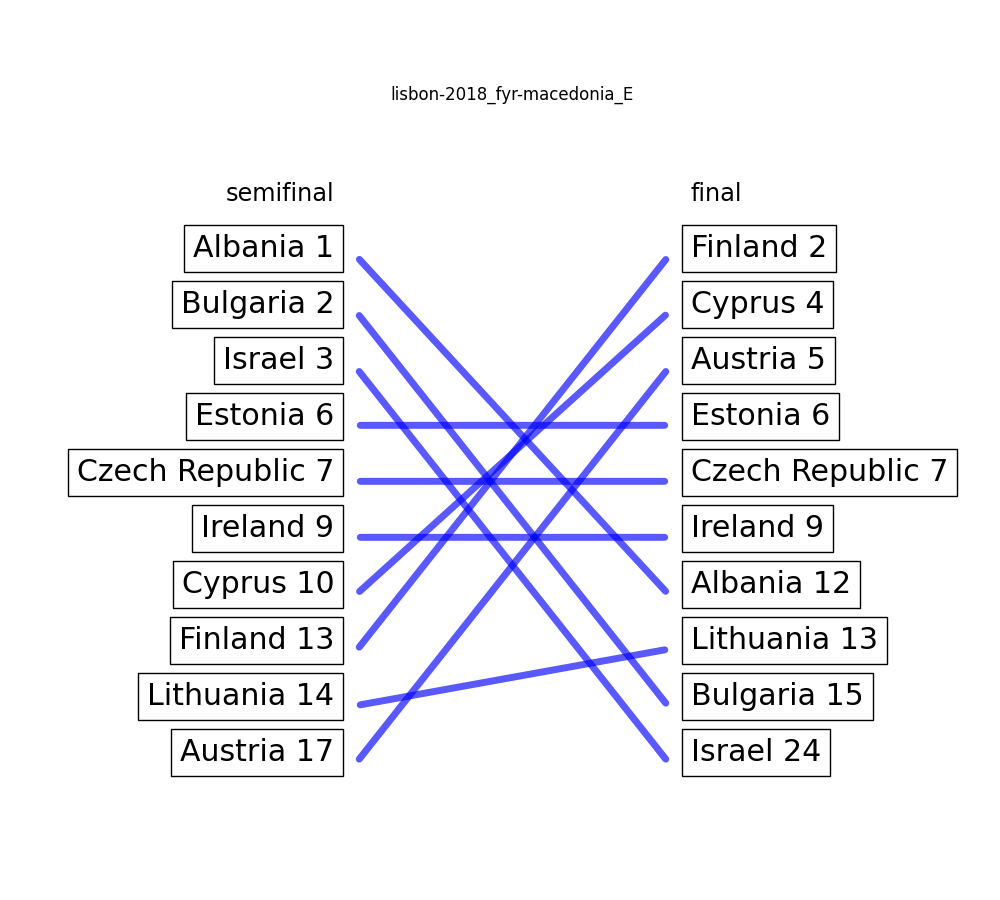

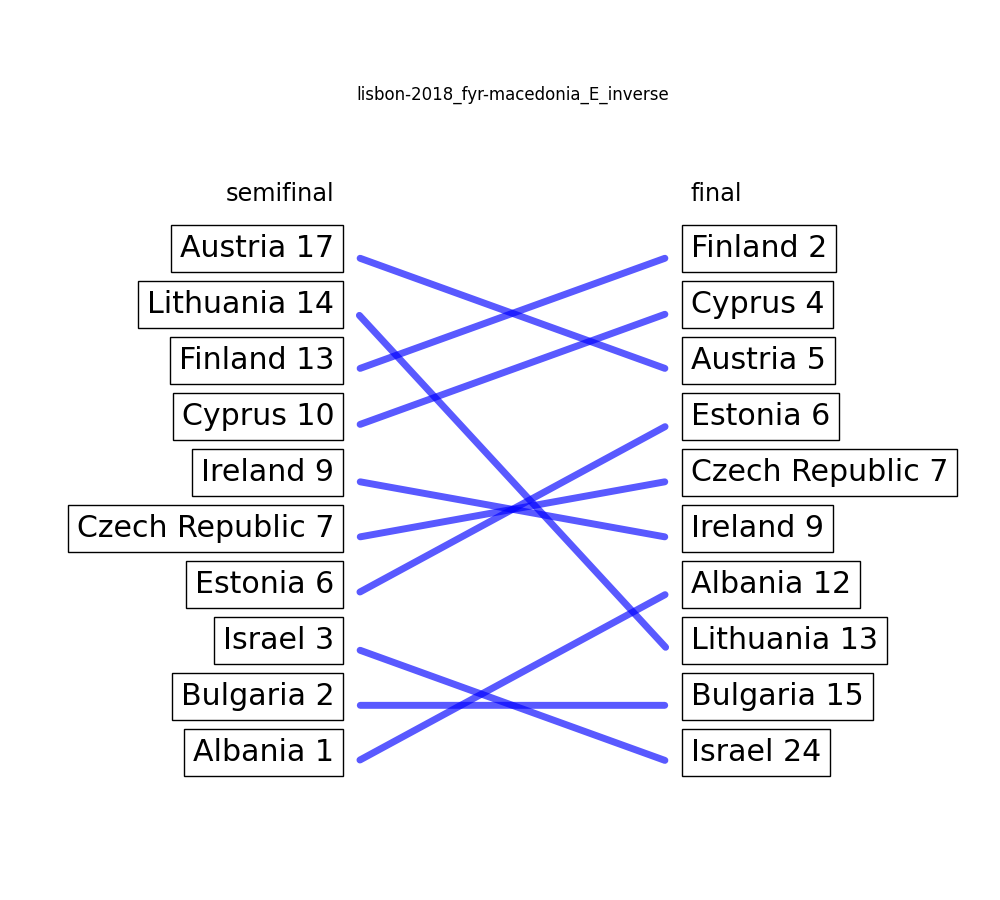

Lisbon 2018: FYR Macedonia E – 7.82 / 10

Now this is a tricky one. What is more plausible: A stable center, and the tops and bottoms switch places? Or three relatively stable groups where just the internal order switches? I do not know.

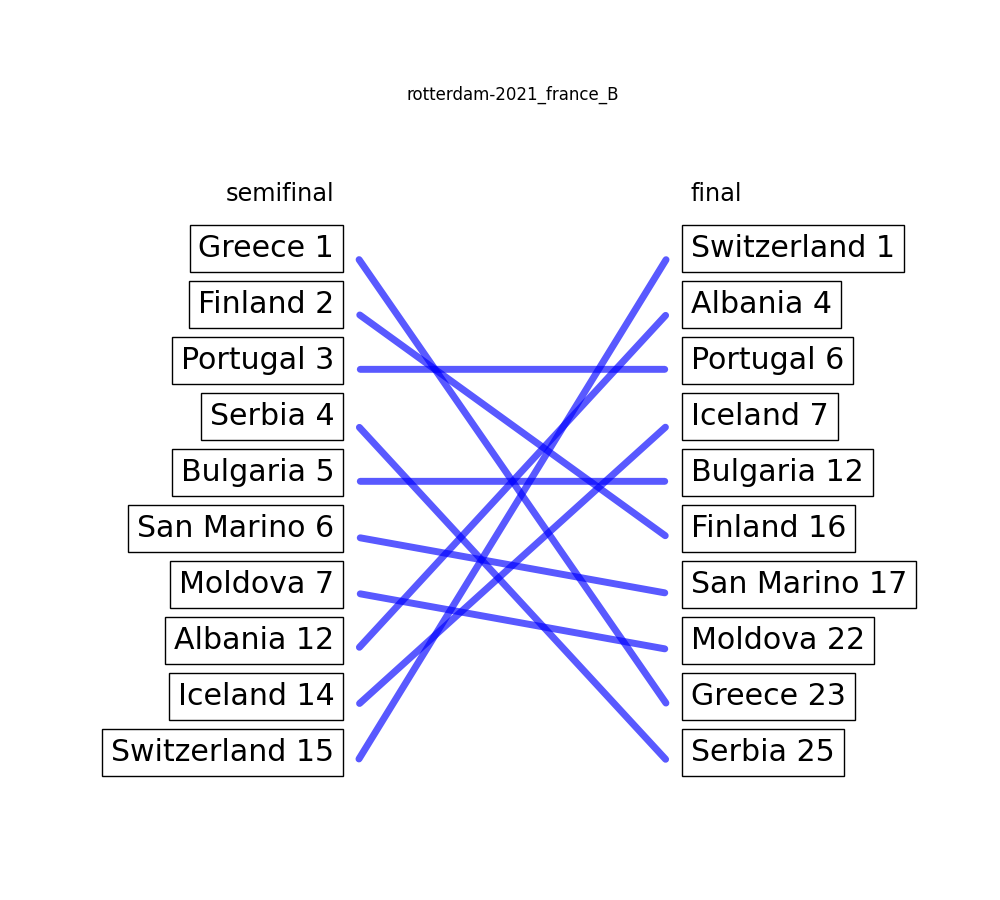

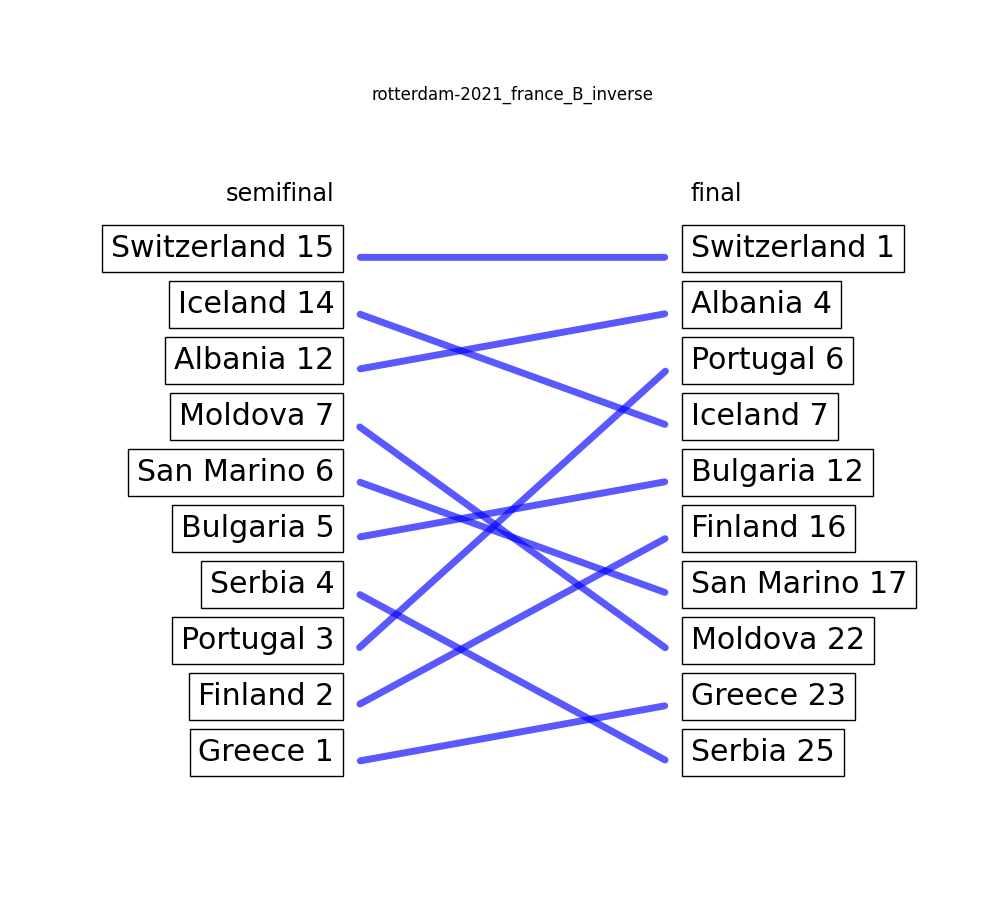

Rotterdam 2021: France B – 7.88 / 10

Now this looks like a clear mis-vote to me. A french jury member that ranks the swiss entry, which has been sung in french, last? Heresy. If we flip the votes from the semifinal, it suddenly looks a lot more in character. A clear blockhead candidate for me.

O wait! It’s Gilbert Marcellus! He is the reason this article exists in the first place.

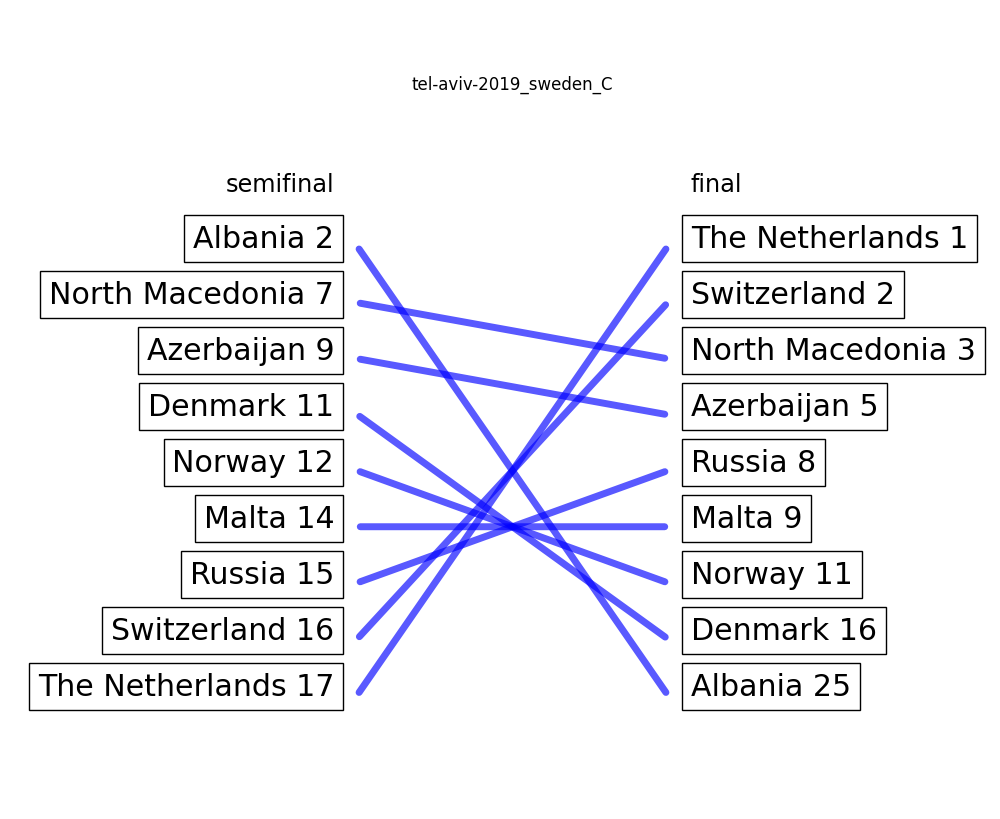

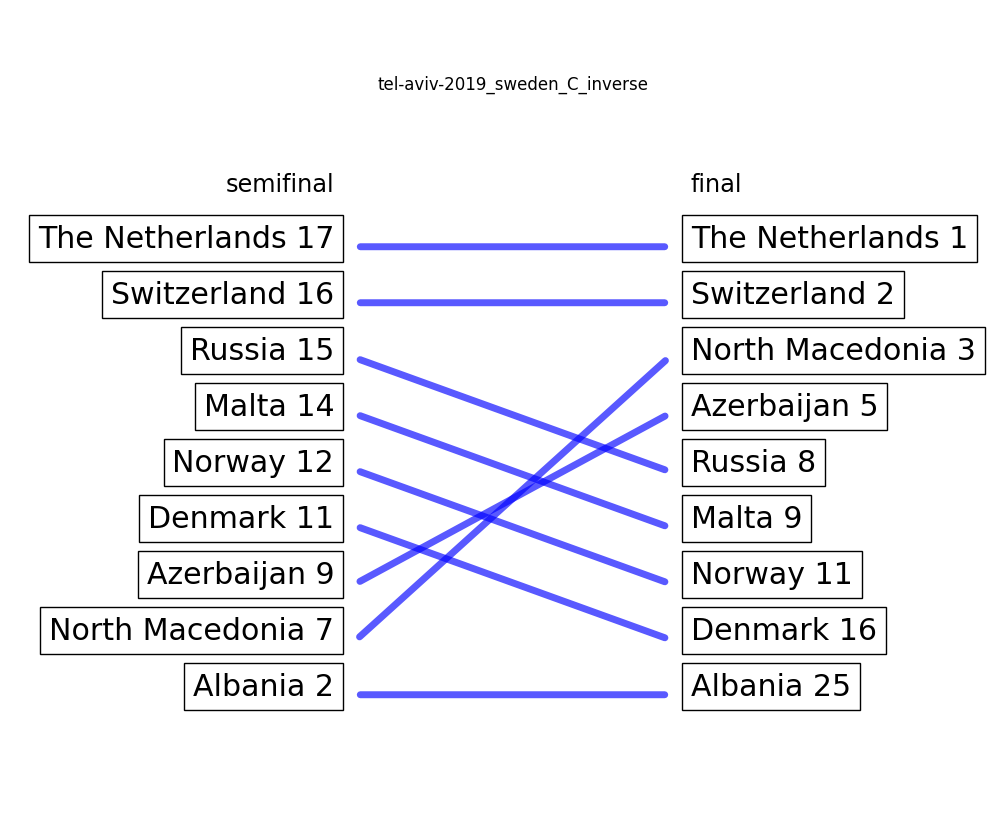

Tel Aviv 2019: Sweden C – 7.92 / 10

We are creeping ever closer to the 8 point mark, and here we have another very clear case of Blockhead voting. If you do not trust me, trust the internet instead.

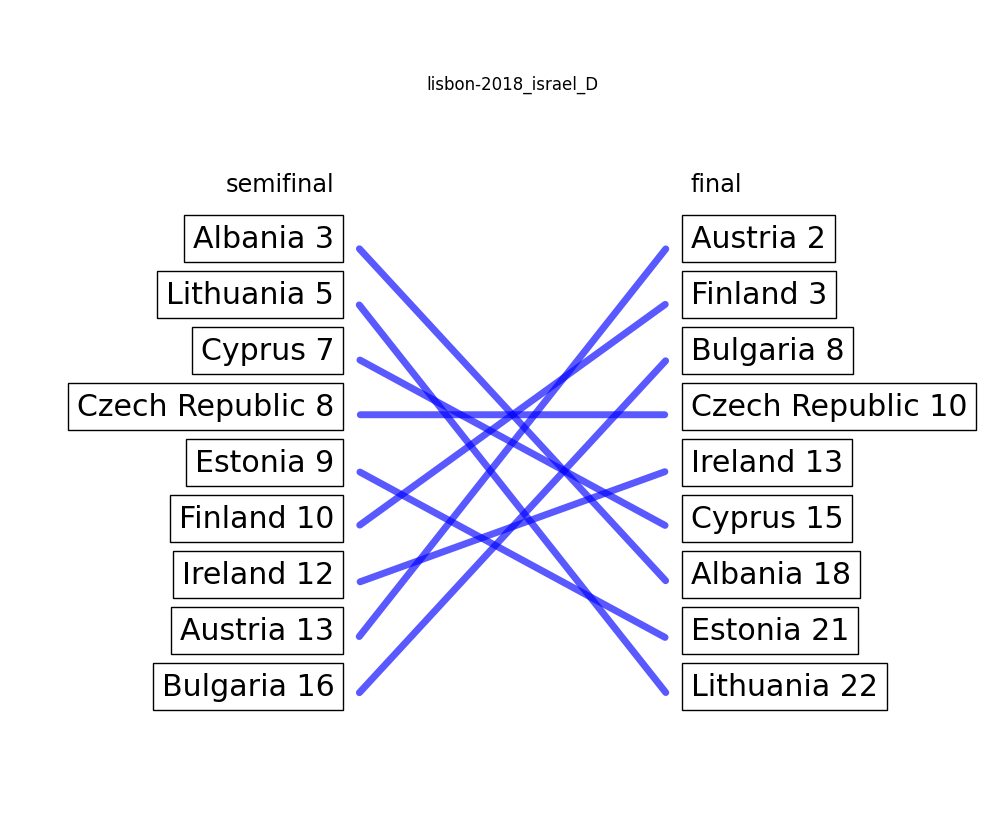

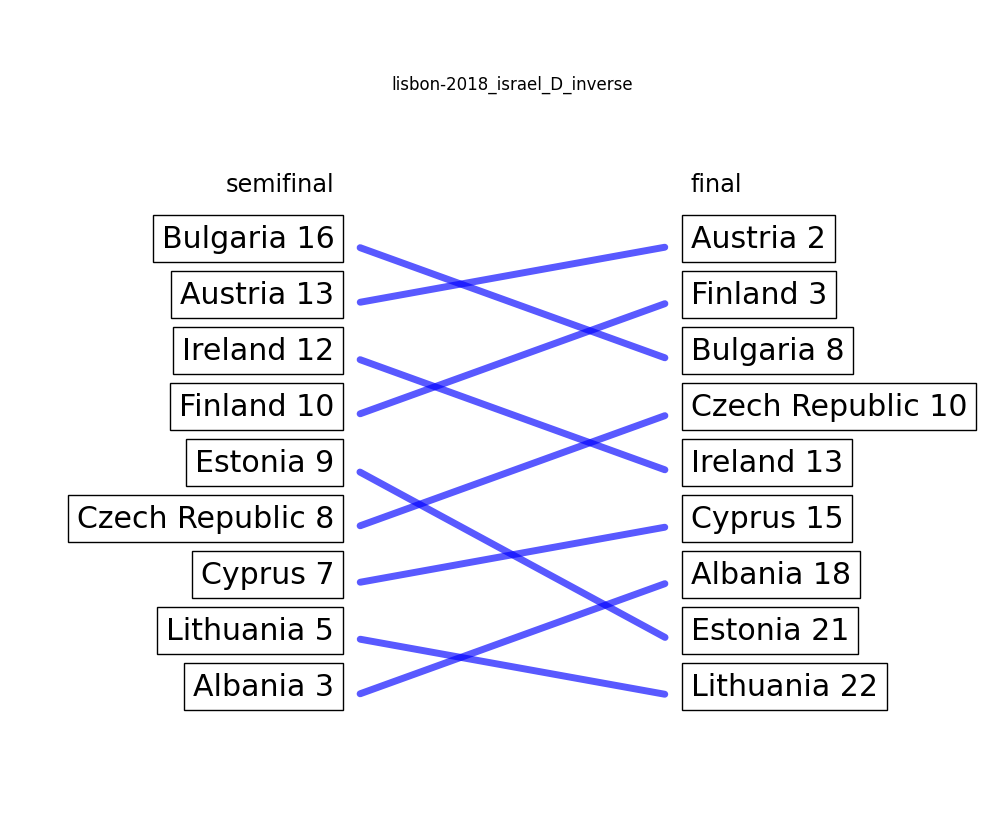

Lisbon 2018: Israel D – 8.67 / 10

Pointwise, we take a big leap forward with this one. What looked somewhat reversed before, looks like a complicated shoelace pattern after the ranks from the semifinal got switched. Definitely highly suspicious.

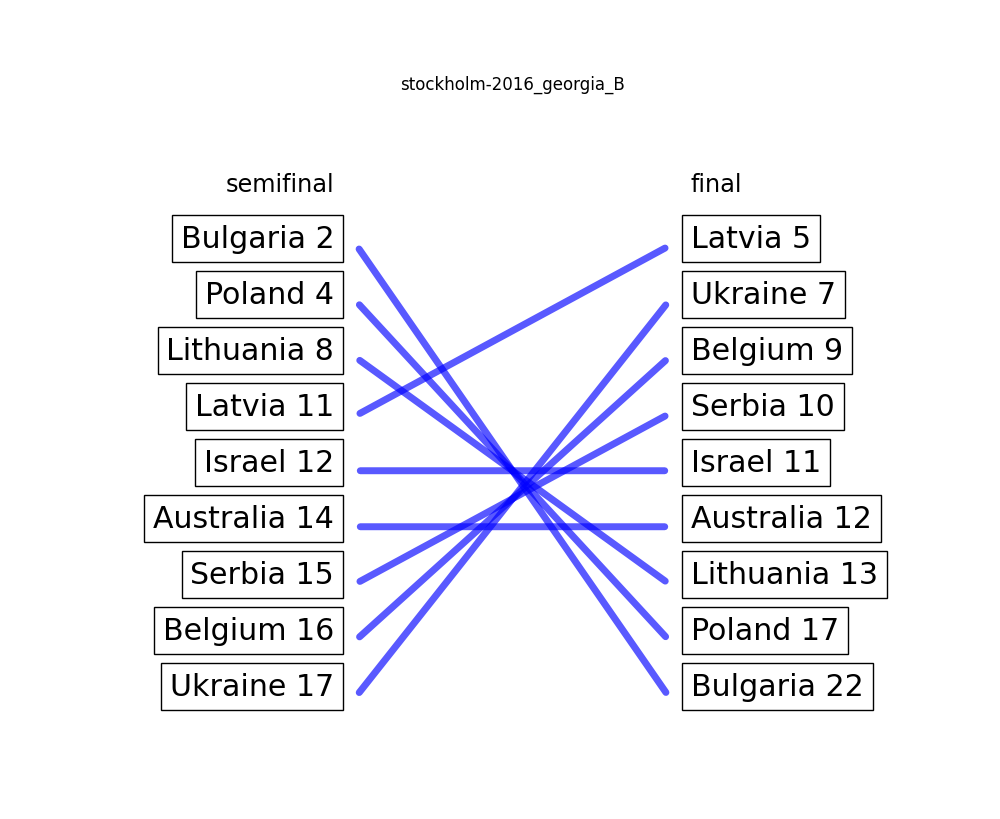

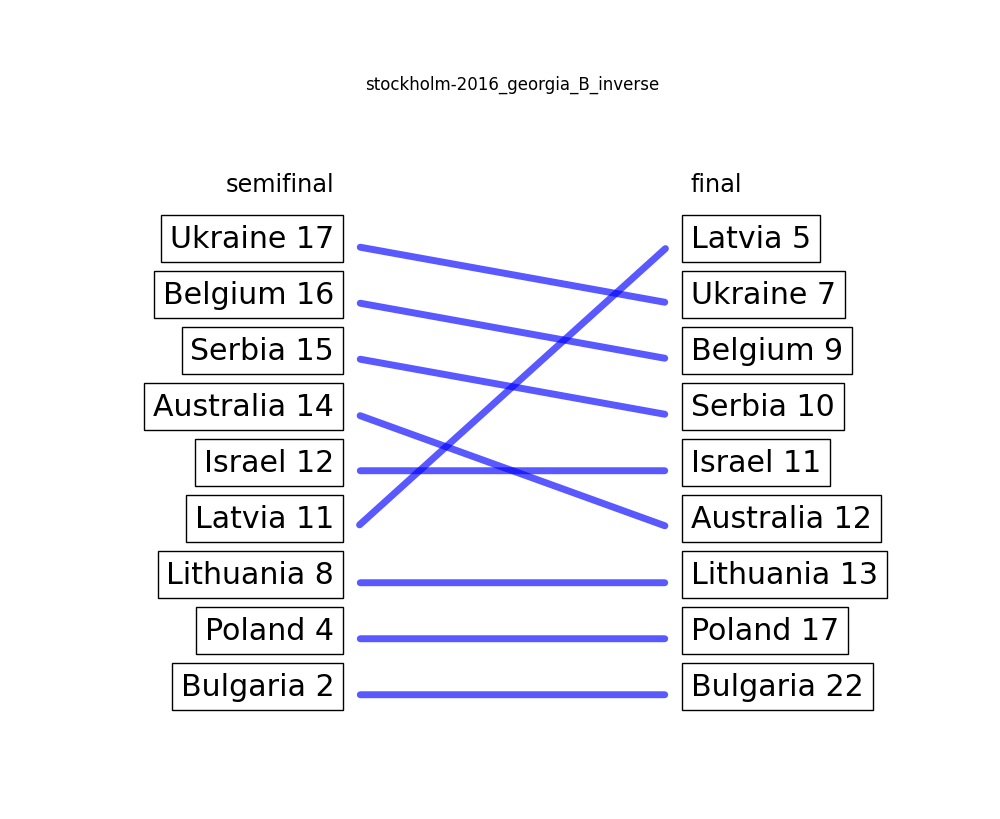

Stockholm 2016: Georgia B – 8.67 / 10

With the same score as the previous jury member, this one seems a lot clearer. Not entirely sure what is up with Latvia there (boop!), but either way we are looking at a clear case of Blockhead voting here.

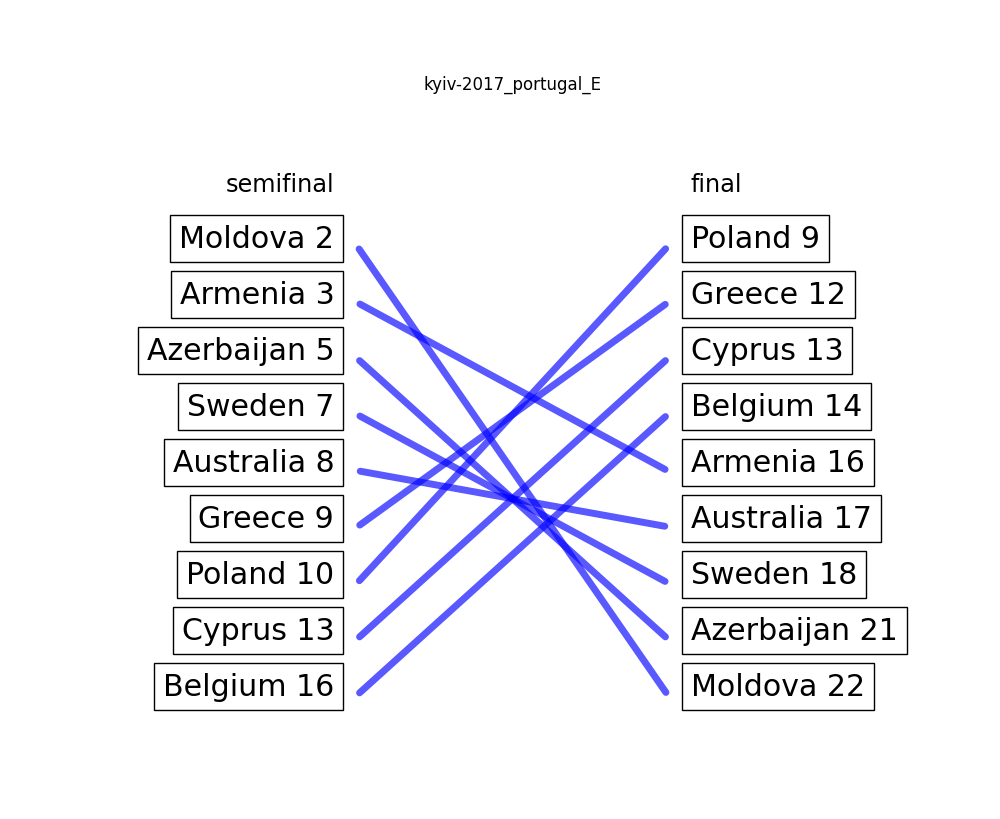

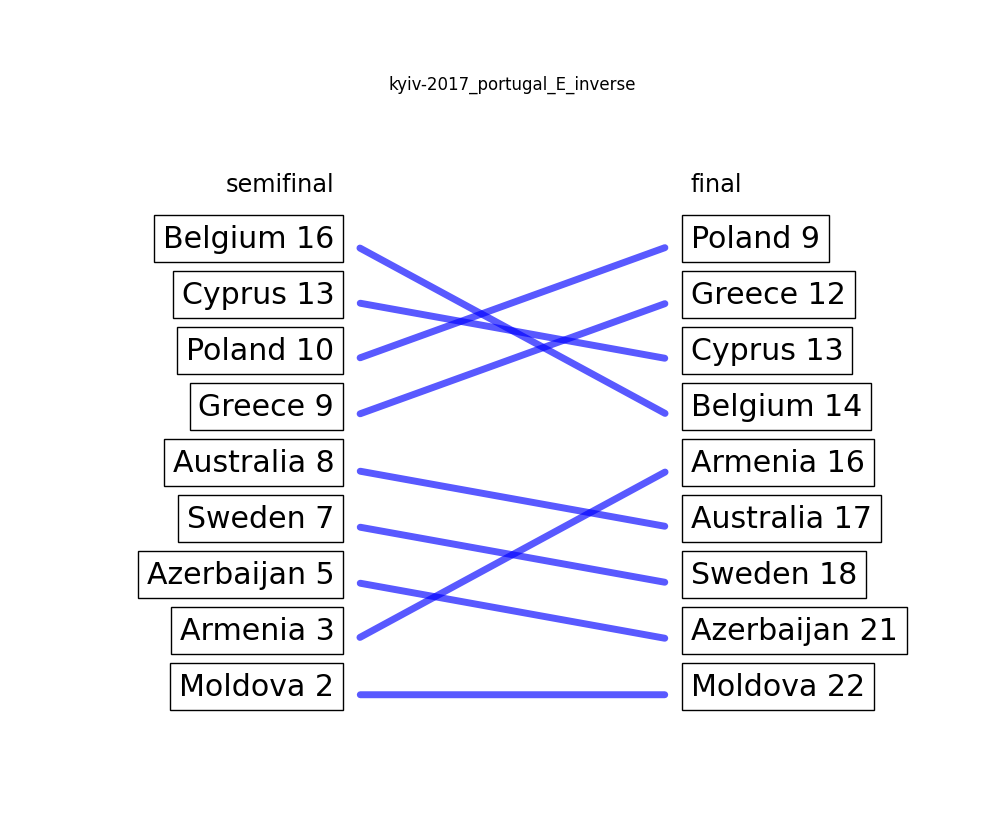

Kyiv 2017: Portugal E – 8.75 / 10

The true atrocity here is not that we are dealing with a case of suspected Blockhead voting, but that this jury member seems to be immune to the saxyness of the moldovan entry.

But hold up. The whole column for this jury member in the grand final looks suspicious. Ranking Croatia first, whereas most other Portuguese jury members rank it towards the end? The same with Romania and Ukraine? This is either spite voting against the other jury members, or an extremely rare case of reverse Blockhead voting. Amazing.

After that high we get to the grand final (hehe) of our investigation.

What we have seen so far included some highly suspicious cases, but our top scorer operates entirely on another level.

Here we go:

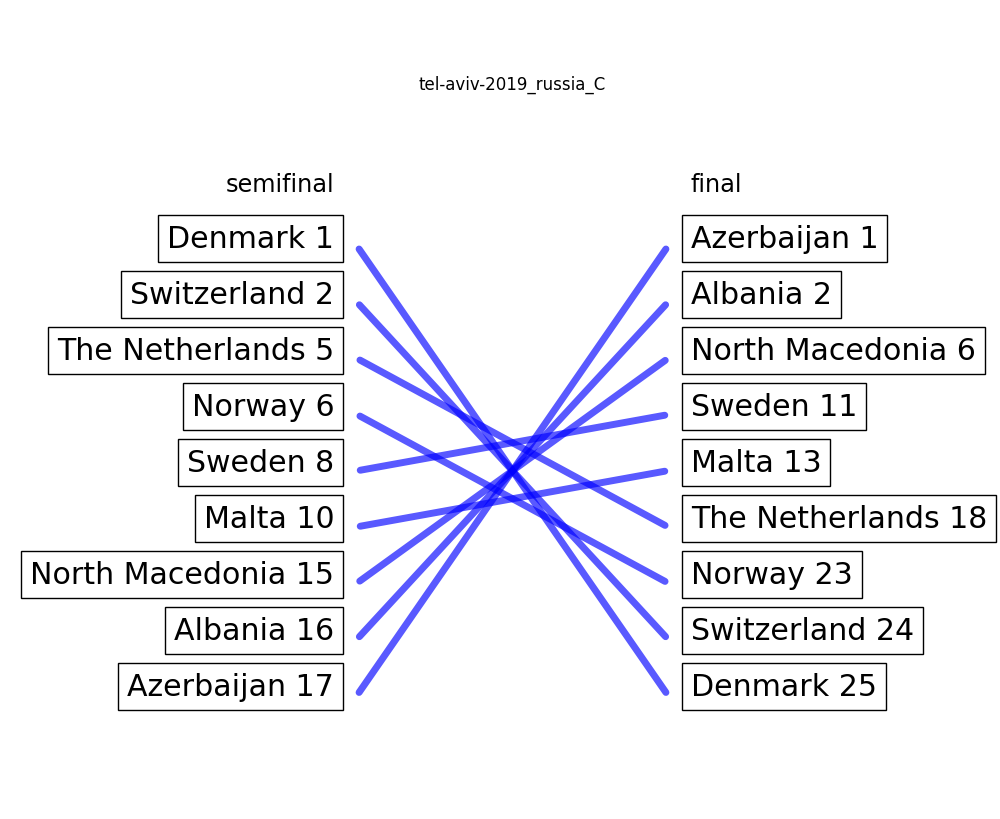

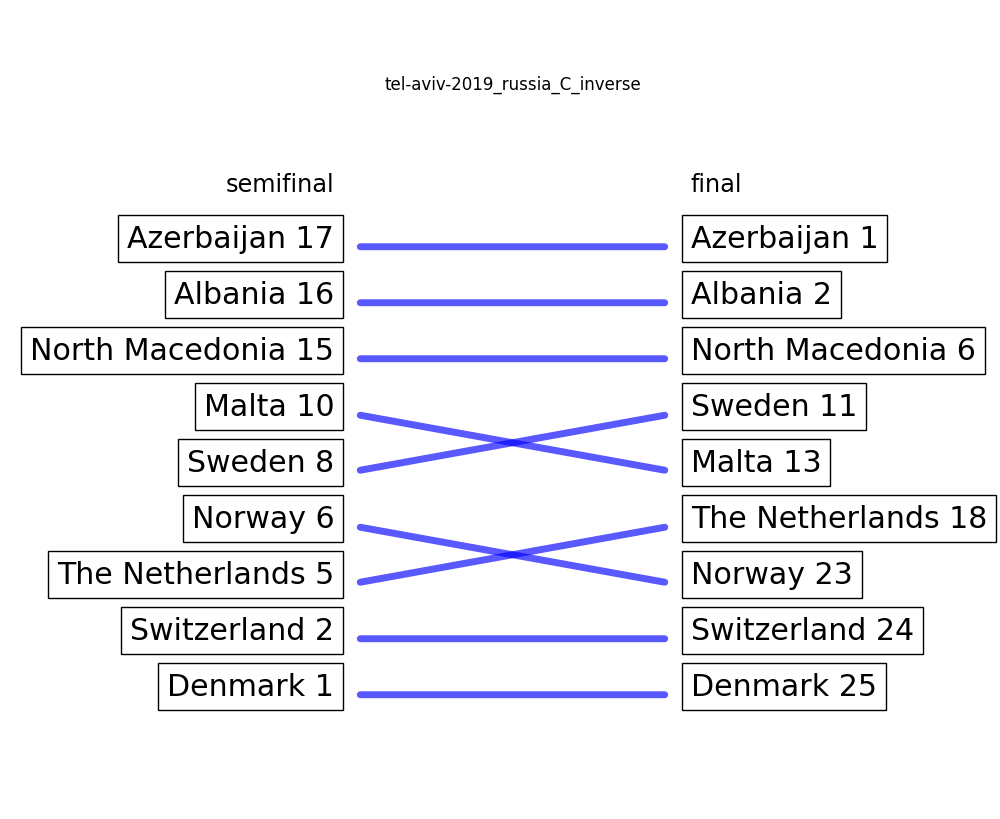

Tel Aviv 2019: Russia C – 9.83 / 10

Barely missing the highest achievable score of 10 / 10, this jury member clearly does not know their tops from their bottoms. This is so blatantly obvious, yet nobody seems to have picked up on it. Probably because ranking countries in reverse order seemed to be an ongoing theme in 2019. Who knows.

Conclusion

I don’t know, seems like we have had some success. Sadly.

Since jury members can obviously not be trusted with putting things into the correct order, and we can only detect it in some cases and only once it is too late, there is only one possible solution: The juries must be abolished. One more reason to add to the list.

- Where “ranking last in the semifinal” of course means the last rank that still advanced to the grand final. Remember, we’re only looking at entries that were ranked twice. ↩

- For completeness: We use the sum of the squares of the numbers of places each entry changes from semifinal to final. We use the square instead of only the absolute value because that puts emphasis on big changes over little changes – bigger number, much bigger square value. ↩