The notes are revealed in no particular order.

Loreen

Congrats to Loreen who wins the contest once again for Sweden.

I have no quarrel with Loreen winning the contest in general.

What I take issue with is Loreen winning the contest as the Jury favourite over Käärijä (Finland), the even clearer televote favourite (more points). The televote has not given Loreen a single 12 points. That is remarkable, and a strong indicator that something is off with this result.

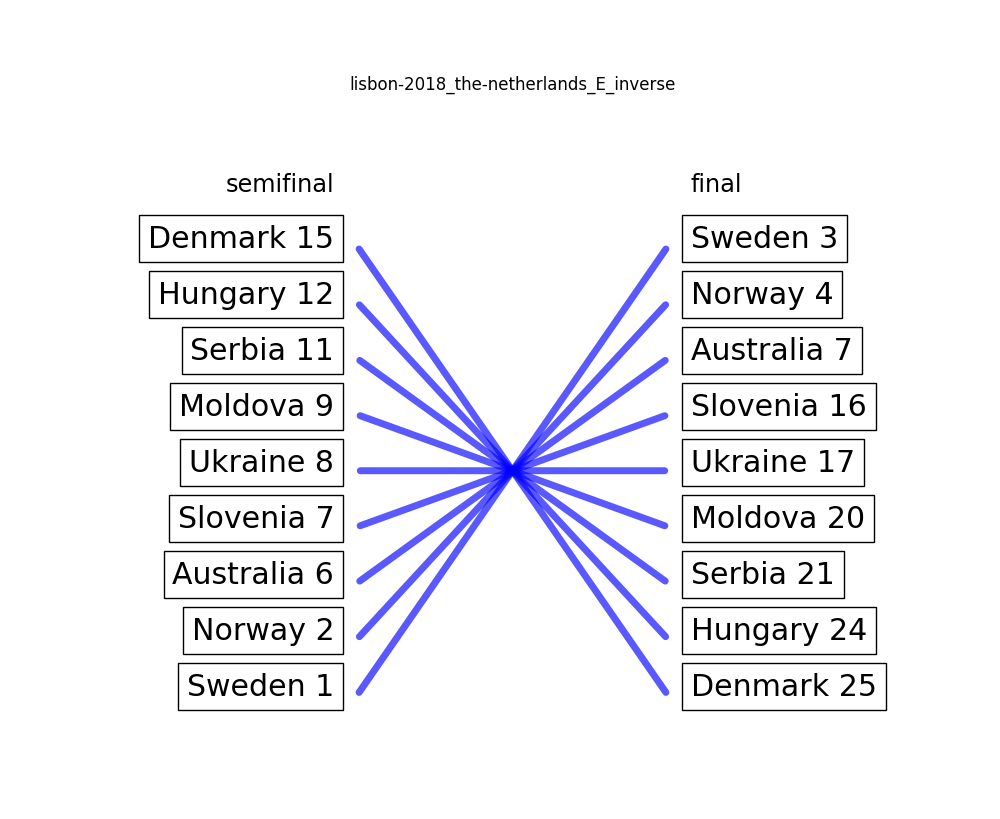

The juries have – repeatedly – demonstrated that they are unfit to fulfil their role at this contest and that they must therefore not be in a position to determine the contest’s overall winner against the expressed will of the people. This is a contest for the people, not for music professionals1. Getting rid of the jury vote in the semifinals is one step in the right direction. Removing the jury vote from the grand final is the logical and necessary next step. It would be fine to record jury votes as a backup, for example if a suspiciously large number of SIM cards is sold in a small country again. Or to use them as a tie breaker in the grand final, for the unlikely event that multiple entries receive the same number of points from the televote. You can even print out a “Jury Winner” certificate on Saturday morning and hand it over to the respective act, like they do with the other awards. Just keep it out of the main show.

Back to Sweden and Loreen. The staging of Tattoo was, well, difficult. All you see on the narrowed screen is Loreen in her little hotbox, getting from a horizontal into a vertical position, singing, shouting against the wind machine, wiggling her prolonged swamp thing fingers. There is a single, short, pointless wide shot at the end. That is it. That is the only point in the performance where you can actually see (if you are not currently looking elsewhere) that this actually takes place on the Eurovision stage, not back in Sweden or in your grandmother’s bathroom. The staging does not need and does not use the big stage and the crowd around it that the contest offers to the artist. It is like if someone walked on stage, popped a DVD into a projector, pressed play, and filmed the screen.

This kind of staging is not new. Eric Saade had an even worse variant for his Melodifestivalen entry in 2022, where even the audience in the arena could not see him until the end when the walls come down. However, this took place towards the end of covid restrictions for TV productions in Sweden, so the staging has been developed in a context where it is not even sure that there will be an actual audience. With that background, such an experimental staging decision is more comprehensible. And we also had Armenia’s Rosa Linn in 2022, who spent the first two minutes of her song in her little post-it room2. But then she went into the hole she ripped and used the stage and the audience for the highlight last minute of her performance.

Unlike Loreen.

Switzerland

We briefly stay at the topic of staging. Switzerland’s Remo Forrer sang his song “Watergun” and the staging was choreographed by Sacha Jean-Baptiste3. But one part seemed awfully familiar…

Screenshot: Eurovision Song Contest / YouTube

Screenshot: EurovisionFanTV / YouTube

It has been twenty years. Surely nobody will remember?

Points

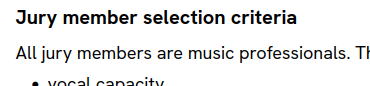

Two acts in the second semi-final received zero points from the televote, and therefore zero points overall: Piqued Jacks for San Marino, and Theodor Andrei for Romania. Undeserved of course, because no participant in the Eurovision Song Contest deserves zero points. But well, it is not the greatest surprise.

I am by the way still looking for that video edit of the Romanian entry where Theodor gets body-checked off the stage by the golden sprinter with the dirty hands. If you see one, tell me pls.

Germany’s Lord of the Lost came last overall with 18 points total, while getting more televote points (15) than two other entries (9 – UK, 5 – Spain). Ah, the joy of combined voting results. And yet another opportunity to blame the juries.

Austria

Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe

Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe

Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe

Edgar Allan, Edgar Allan

Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe

Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe

Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe, Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

Norway

And Finally

Danke, Stefan. Ich habe es sehr gemocht.

- Music professionals with at times questionable expertise or selection criteria, I must add. ↩

- The room was actually just a rotatable half of a room. ↩

- As was Sweden’s, apparently. Turns out if you’re staging everything™ you’re getting all the hate, too 😗 ↩